Remembering Elwood Higginbottom: Speakers call for systematic change at plaque unveiling

Published 9:49 am Tuesday, October 30, 2018

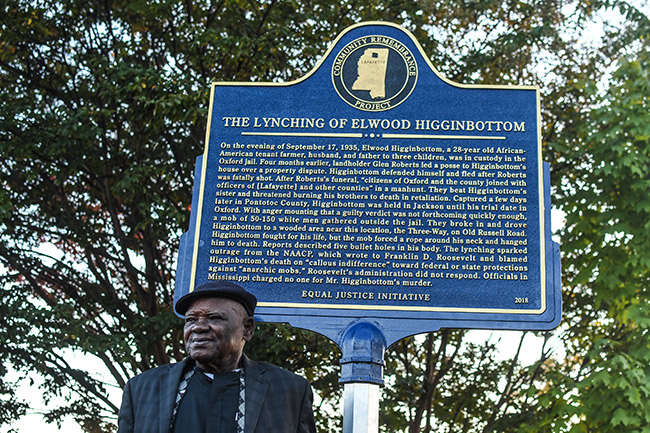

- E.W. Higginbottom, son of Elwood Higginbottom, stands near a marker that was placed near where it is thought that Elwood Higginbottom was lynched, in Oxford, Miss. on Saturday, October 27, 2018. The marker was erected following a ceremony earlier in the day at 2nd Baptist Church. Elwood Higginbottom was lynched in Lafayette County, Miss. on September 17, 1935. (Bruce Newman)

By Lasherica Thorton

EAGLE Contributor

Second Baptist Church lies less than a mile away from where the last lynching in Lafayette County took place at the three-way intersection of North Lamar Boulevard and Molly Barr Road in 1935.

Trending

Saturday, both blacks and whites filled the rows of that church to remember the seventh and last known lynching victim, Elwood Higginbottom, and witness the unveiling of a lynching memorialization plaque.

Though the topic was heavily weighted, the crowd took to its feet in standing ovation several times as many speakers called for systematic change.

“It’s so important for us to be able to understand our contemporary challenges through the lens of our history. If we want to know how we move forward and heal, we really have to immerse ourselves into truth telling,” said Kiara Boone of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) . “Sometimes, that truth is difficult. Sometimes, that truth is painful. And, sometimes, that truth is hurtful, but it’s always the truth.”

The EJI is a non-profit organization based in Montgomery, Ala. that provides legal representation to prisoners possibly wrongly convicted, poor prisoners without effective counsel and others that may have been denied an unfair trial.

The EJI was one of many responsible for the creation of the plaque, including Lafayette County community members, the Higginbottom family, the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation and the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project, all of which had representatives at the unveiling ceremony.

Now, when people come to Oxford, they will know the story of Higginbottom, said Boone.

Trending

Higginbottom, a 28-year old tenant farmer, father and husband was killed and hanged by a mob of more than 50 on Sept. 17, 1935 when the group broke into the jail where he was held. He was on trial for shooting his landholder in self-defense, and the mob attacked when a guilty verdict was not forthcoming, the plaque reads.

However, no one was ever prosecuted for Higginbottom’s murder.

After the lynching, Higginbottom’s surviving family fled Oxford, and only one of his three children, 87-year old E.W. Higginbottom, is still living. Nevertheless, the Higginbottom legacy lives on as family members and descendants from Memphis and as far as Texas and Ohio sat in the front of the packed church to remember Elwood Higginbottom.

But, with each individual who took the microphone during Saturday’s ceremony, there was a call for systematic change.

Just as Kevin Frye, a lawyer and member of the Lafayette County Board of Supervisors, called out the failures of the justice system, also evident in the case of Higginbottom, Evan Millgan of EJI later asked, “Why are we so comfortable having a system where so many people are thrown away?”

Diane Harriford, a professor at Vassar College and a part of Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project, voiced the need to get to the root of what’s going on with racial violence.

Even the host Brian Foster, representing the Steering Committee, clinched his fist as the symbol for black power, looked at the descendants of Higginbottom and said “Y’all are proof that they couldn’t kill us all.”

The ceremony wouldn’t close, however, without the crowd saying the name of Elwood Higginbottom as his cousin Louis Burroughs remembered him.

Burroughs, of Cleveland, Ohio, learned of his relationship to Higginbottom only after reading a New York Times magazine piece.

Upon learning of him, Burroughs saw that the media of that time presented a false narrative of Higginbottom as an angry, illiterate sharecropper needing to be humanized. However, his family remembers him as intelligent, ambitious and strong.

To Burroughs and his family, he was a hero, who protected his family when the landholder led a posse onto his property.

Although it was a name he never knew before that magazine piece, he proudly said the name of Elwood Higginbottom, his ancestor.

As Higginbottom never got to see the last days of his trial and was lynched by a mob, Burroughs asked the attendants to consider the problem.

“What would have Mississippi looked like today if white citizens had not chased down and criminalized for hardly any reason the black population? What if African Americans had not been systematically killed for exercising basic human rights in Mississippi?” he asked, “What would the state look like today if white supremacy wasn’t the law of the land? What would the City of Oxford and the town square look like if the Confederate soldier was replaced by a monument to the brave black men of Mississippi?”