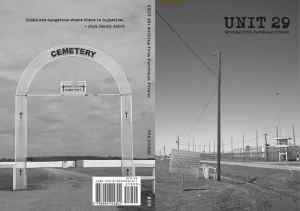

Unit 29: Writings from Parchman Prison: Stories Seldom Told

Published 9:27 am Friday, March 21, 2025

- The book is the culmination of three years of working with incarcerated students through VOX’s prison outreach program, Prison Writes Initiative.

The Oxford non-profit art organization, VOX PRESS, has released a collection of prison writings, “Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison.”

The book is the culmination of three years of working with incarcerated students through VOX’s prison outreach program, Prison Writes Initiative.

The collection is comprised of writings from over 30 inmates housed in Unit 29 at Mississippi State Penitentiary (Parchman Farm). The book delves into the aftereffects of the infamous riots in Unit 29 from December 2019 through April of 2020, and how those housed there deal with the conditions of trying to live in one of the country’s most notorious prison facilities.

The collection is comprised of writings from over 30 inmates housed in Unit 29 at Mississippi State Penitentiary (Parchman Farm). The book delves into the aftereffects of the infamous riots in Unit 29 from December 2019 through April of 2020, and how those housed there deal with the conditions of trying to live in one of the country’s most notorious prison facilities.

Trending

Unit 29: Writings from Parchman Prison is a collection of essays, poems, and art created by inmates of Mississippi State Penitentiary’s largest unit. It is a compilation created by over 30 detainees over the span of 3 years. Most of the contributors in the book had never created art before– yet produced a harrowing and honest reflection on life while incarcerated. It provides a rare and gritty portrayal of prison realism, with potent commentary on their experiences in Parchman Prison. Each writer in this book has their own distinct narrative voice. The writing covers a variety of topics such as religion, neglect, trauma, violence, and suicide. Though, the majority of the book contains the students’ experiences and encounters while in Parchman.

This book was made possible by the VOX Press and their educational outreach program, Mississippi Prison Writes Initiative, a small non-profit from Oxford Mississippi. Since 2002, VOX director Louis Bourgeois has a long history of working with incarcerated persons in writing workshops and began a creative writing class at Parchman Prison. Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison was created under Bourgeois’ instruction, with some mentions of him throughout the book by his students. Over the last ten years, three volumes of Mississippi inmate writing have been published through VOX. The explicit purpose of VOX Publishing and the Prison Writes Initiative is to provide a voice for the unheard and to publish marginalized writers.

Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm, is 20,000 acres with deep roots in American slavery. Originally a plantation, in the early 1900s Parchman got its beginnings functioning as a prison farm utilizing inmates for hard labor. Today, it consists of mostly open fields, a few trees, ponds and seven different housing units. The prison is located in the Mississippi delta region of Sunflower County on a desolate stretch of Highway 49. The book’s focus, Unit 29, is the largest unit of Parchman. It is surrounded by high razor-wired chain-link fences and four guard towers. Bourgeois describes the inside as chaotic, consisting of ten-tiered zones with a caged-in prison yard. The cells are dirty and there is a constant smell of marijuana, tobacco, and a general air of smoke. It is never silent, with the TV’s bolted to a center pillar always blaring and inmates shouting at each other across from their cells.

The artwork included in the book are black and white pencil drawings depicting inmates lives and Parchman itself. Some are drawings of the outside, depicting the guard towers.

Many have religious tones, with drawings of Jesus’ crucifixion, demons, doves, the Bible, and inscriptions of prayer. Others include drawings of decrepit cells with the point of view being behind bars. The point of view makes one put themselves in the position of the artist, creating a sense of constriction and imprisonment– evoking empathy. The rendering of Parchman by the artists is distinct– providing a visual element that testifies to the writing’s brutality.

Many wrote about their living conditions including floods, random fires, leaking ceilings, showers three times a week, and no air conditioning and minimal heating. In two separate essays, student Larry Jenkins described the food as horrible, barely enough with bugs, halfway done, and, “It seems like they take the smallest amount of money that the government provides for us and buy the cheapest food they can find to feed us.” There is ineffectual medical and mental health care. One prisoner wrote of a random fire that filled the building with thick smoke. After the fire was put out, no one received any medical care for the smoke inhalation. Another wrote that in 2004, the prisoners were forced outside in the rain and unable to move from their position without being beaten due to a prisoner being murdered.

Trending

An elderly man died that day from being beaten. The writer Matthew Moberg expanded on the lack of medical care, saying there is one mental health doctor for 800 inmates, making it impossible to assist them.

Since the inmates spend nearly 24/7 in their 6×6 cells, boredom runs rampant throughout Parchman. To quell this, some turn to prayer, pacing, drawing, writing, reading, and attending classes. Others turn to drugs. Alcohol, crystal meth, marijuana, and designer drugs like spice and bath salts are almost always readily available. Some came to Parchman with addiction, and was the reason for their incarceration.

Some become addicts while in Parchman, seeking out drugs to cope. For those with addiction, there are little to no opportunities for recovery. Other contraband available to inmates are cell phones used to contact their families and subdue the boredom. One inmate wrote of believing cell phones have changed Parchman for the better, as they give the inmates a motivator to stay out of trouble.

Some wrote about their time in solitary confinement, commonly known as “the hole.”

Solitary confinement is meant for discipline and to break people down. Most days are spent entirely in a cell, with three days available to go to the yard. Many convicts in long-term segregation have digestive problems due to the food, dehydration, and lack of physical activity. The food is in small portions and cold. Most convicts lose considerable amounts of weight as well. Excess and long-term solitary confinement is extremely damaging to the body and mind, which is reflected in some of the writing in the book.

During 2020, there were more deaths at Parchman than in the last 20 years. Suicide, murder, lack of medical attention. Whatever the cause you can bet on one thing, Parchman has them all — Matthew Moberg

Death is not uncommon in Parchman and suicidal ideation is a heavy theme throughout the book. The essay “Prison Violence and Death” by Matthew Moberg describes some of the causes of death in Parchman. One cause of death is murder, Moberg wrote of witnessing his friend being beaten to death. Another is lack of medical attention with some inmates having diabetes and not receiving a proper diet. Spiders are another source of death. Moberg recounts being bitten by brown recluses and seeing snakes, bats, frogs, and mosquitoes. The most major cause of death written about by Moberg and many others, is suicide. Depression is common, knowing you’ll never be free or hold your family again can make someone want to give up. One poem titled “4 Walls” follows a rhyme scheme and describes depression, loneliness, and suicidal intentions. In almost all of Christopher Smith’s writings – whom the book is dedicated to– he writes about taking his own life.

He wrote of being on suicide watch and his multiple attempts. Smith did eventually take his own life.

Another inmate wrote of two hangings he witnessed, one he believes could have been preventable by the corrections officers, but “they got tired of dealing with him.”

Under all of these conditions and unfortunate circumstances, some writers had a hopeful outlook. Many wrote of religion, and how it keeps them alive in a place like Parchman. In one essay titled “My Prison Walk” by Leon Johnson described a band named Full Pardon that plays in the gymnasium and for multiple other units. In Steve Wilbanks’ essay “Scars,” he wrote of the positives of solitary confinement. Wilbanks describes how being in the hole gives you time to think, learn, grow, and heal. The classes offered in Parchman are a positive side as well. Wilbanks took a paralegal certification course, helping him in his attempts to appeal his conviction. Some receive their GEDs and get a graduation ceremony. The effort and dedication it takes for education in prison is difficult, yet it is possible, and it has a much stronger positive effect than most would realize. An example being this book, as it gives a creative and therapeutic outlet in dire circumstances.

In a place like Parchman, moving forward seems impossible. It is built on adversity, and curates a harsh and violent culture. Yet, many write of their resilience. They describe efforts they have taken to better themselves and keep a strong mind. Efforts they have taken to reach forgiveness in themselves. Much of these efforts are religious. The student’s hopeful outlooks create a captivating contrast with the darker writings. Some of the writers in this book have been released, some are still in Unit 29, many have been transferred, and a few have died over the course of compiling the book. From this project, some have become devoted to writing and will have their individual stories published through VOX.

This book is not for the faint of heart. It is a shocking and tragic representation of life in one of America’s most notorious prisons. It contains heavy themes of suicide, death, drugs, and a plethora of other things. The material spans from narrative essays and poetry to talented pencil drawings and skilled rhyme schemes. The dark portrayals are mixed with hopeful sentiments; making the book full of complex and thought-provoking outlooks. It humanizes the writers and artists, making it capable to view them as individuals rather than a prisoner or a statistic.

Unit 29: Writings from Parchman Prison is available online at www.voxpress.org and on Amazon.