Celebrating the centennial of two Mississippi legends

Published 1:59 pm Monday, January 13, 2025

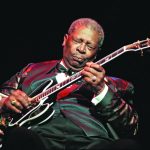

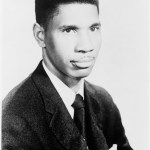

In 2025, Mississippi will proudly commemorate the centennial birthdays of two of its most iconic figures— Riley “B.B.” King and Medgar Wiley Evers—whose profound legacies continue to inspire generations.

On January 14, Senator John Horhn and Representative Otis Anthony will present a resolution enacted by both the Senate and the Mississippi House of Representatives honoring King and Evers in the Rotunda of the Mississippi State Capitol in Jackson at 10 a.m.

The public is invited to attend.

Trending

An array of events will be sponsored during 2025 by the B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center in Indianola, Mississippi, and the National Park Service Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument and the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute in Jackson, Mississippi. Various programs will celebrate the men’s birthdays, with Evers’ on July 2nd, and King’s on September 16th.

B.B. King was born in the Mississippi Delta in Berclair and lived part of his young life about sixty miles to the east in Kilmichael, Mississippi. His interest in music began in the Holiness Church where he was introduced to the guitar. He moved to work on a plantation near Indianola, and it was there that he joined a gospel group that performed on local radio stations. Riley wanted more, and in 1946 he ventured to Memphis to see if he could make it as a musician, but he found too much competition.

He returned to Indianola for a short time, but Memphis still beckoned. His second trip there in 1947 resulted in his finding work at a West Memphis nightclub and eventually a job as deejay with radio station WDIA. This stint began his nickname as “Beale Street Blues Boy,” which became shortened to simply “B.B.” His popularity did not go unnoticed and a record contract soon followed.

As King began to tour widely in the United States and internationally, he became a supporter of civil rights. He had friendships with Dr. Martin Luther King as well as Medgar Evers, and helped Medgar’s brother Charles organize the Medgar Evers Homecoming Festival, where he also performed for many years.

Always calling Indianola his hometown, he graciously held annual homecoming concerts there for years at no cost. He was noted by “AllMusic” as “the single most important electric guitarist in the last half of the 20th century.” He received a Kennedy Center Honors Award, fifteen GRAMMYs, the GRAMMY Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, among many other noted recognitions. He performed more live concerts than any other recording artist ever has, and likely ever will. In the 1950s, he would perform more than 350 shows per year. King would eventually perform in more than ninety different countries.

In 2008, the B.B. King and Delta Interpretive Center opened in Indianola to honor its native son, and so far it has welcomed visitors from every state in the U.S. and at least ninety foreign countries.

Trending

Its poignant films, fascinating exhibits and interactive displays tell the story of a young man from an impoverished background whose life far exceeded his dreams. The museum’s programming focuses on educating youth to have opportunities that were not available to King during his early years. King is also buried on the grounds of the museum, carrying out his final wishes.

A native of Decatur, Mississippi, Medgar Evers enlisted in the U.S. Army when he turned 18. He survived enemy fire on the beaches of Normandy and became part of the Red Ball Express, which provided critical supplies to soldiers as they propelled German forces out of France. He spent his whole time fighting the Nazis in World War II, only to return home and fight racism all over again in the form of Jim Crow, which barred Black Americans from restaurants, restrooms, and especially from voting booths.

The same day he celebrated his 21st birthday, he and his brother Charles and a number of other Black veterans tried to vote, only to be turned away by an armed white mob. Using the GI Bill, Evers enrolled in Alcorn Agricultural & Mechanical College (now Alcorn College), where he became class president, a member of the debate team and track team, editor of the yearbook, and the editor of the student newspaper, the Alcorn Herald, before graduating with a degree in business administration.

Myrlie Beasley was just a freshman when he met and married her. The couple moved to Mound Bayou, Mississippi, where Medgar worked for his mentor and civil rights leader, Dr. T.R.M. Howard. Evers sold insurance to those working as sharecroppers and also taught them how to register and vote. He helped carry out a campaign in the Mississippi Delta, encouraging Black drivers to stop buying gas where they couldn’t use the restroom.

In January 1954, he attempted to enroll in the University of Mississippi Law School and was turned down because of the color of his skin. He considered suing, but the NAACP was so impressed with him that the organization hired him as its first field secretary in Mississippi.

He and his family moved to Jackson, and his name soon appeared on a death list circulated by the Ku Klux Klan. When Jackson’s white mayor insisted that all of those taking part in civil rights protests were “outsider agitators,” Evers appealed to the FCC, which granted him equal time to respond. On television,

Evers responded that he and other Black Mississippians were far from “outside agitators;” they simply wanted the state to stop treating them as “second-class citizens.” He explained to viewers that change had begun. “In the racial picture things will never be as they once were,” he said. “History has reached a turning point, here and over the world.”

The same night he spoke, a firebomb was tossed in the driveway of the Evers’ home, where his wife and three children had been watching him speak on television. His wife, Myrlie, put out the fire before the bomb exploded. The same night that President John F. Kennedy delivered his first civil rights speech on June 11, 1963, Evers was shot in the back after arriving home from a civil rights meeting. His wife and children rushed outside and saw him bleeding to death on the driveway. At the request of President Kennedy, Evers was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Meanwhile, his assassin, Byron De La Beckwith, walked free after two 1964 trials. At the urging of Myrlie Evers, Beckwith was tried again in 1994, and this time, he was convicted.

In 2016, the National Park Service named the Evers family home at 2332 Margaret W Alexander Drive a national historic landmark. Four years later, the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument became the 423rd unit of the National Park System. It is now open for tours at selected hours on Tuesday through Saturday.

Reena Evers-Everette, daughter of Medgar Evers and co-executive director of the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute, said, “My father was taken from us far too young, and with so much more work to do. This year, his 100th birthday is a call to action, a call to arms for us to continue diligently advocating for social justice for all. I envision my father still passionately advocating for society’s inequalities. This year will serve as a recognition of what my father did, what his actions gave us as a community and nation, and a

clarion call to honor his legacy and continue his work.”

Malika Polk-Lee, executive director of the B.B. King Museum, said, “I’m thrilled that we get to play a significant role in celebrating what would be the 100th birthdays of Mr. King and Mr. Evers. Through the museum’s programming and events for the year, we want to ensure that Mr. King’s contributions to music and humanity are long remembered.”