Ole Miss student seeks to help children with incarcerated parents

Published 3:02 pm Wednesday, May 9, 2018

By Haley Myatt

It had been over three months since Asya Branch had seen the eyes of her father. It had been too long since she had been able to feel him embrace her in a warm hug; too long since she could reach out at a moment’s notice and hold his strong, working hands in hers.

“Is that daddy?” Her four-year-old sister inquired at their first visitation. It had been too long for her baby sister to even remember what he looked like. But Branch was old enough to remember everything.

She was ten years old when her house was ransacked by government cars and the world as she knew it was flipped upside down. She never thought the man who was always there to tuck her in at night and attend her singing recitals would be confined to only an hour’s conversation once a week behind steel metal bars.

“It was heartbreaking and depressing, but right now, in this moment of time, I think of it as a blessing in disguise,” Branch said.

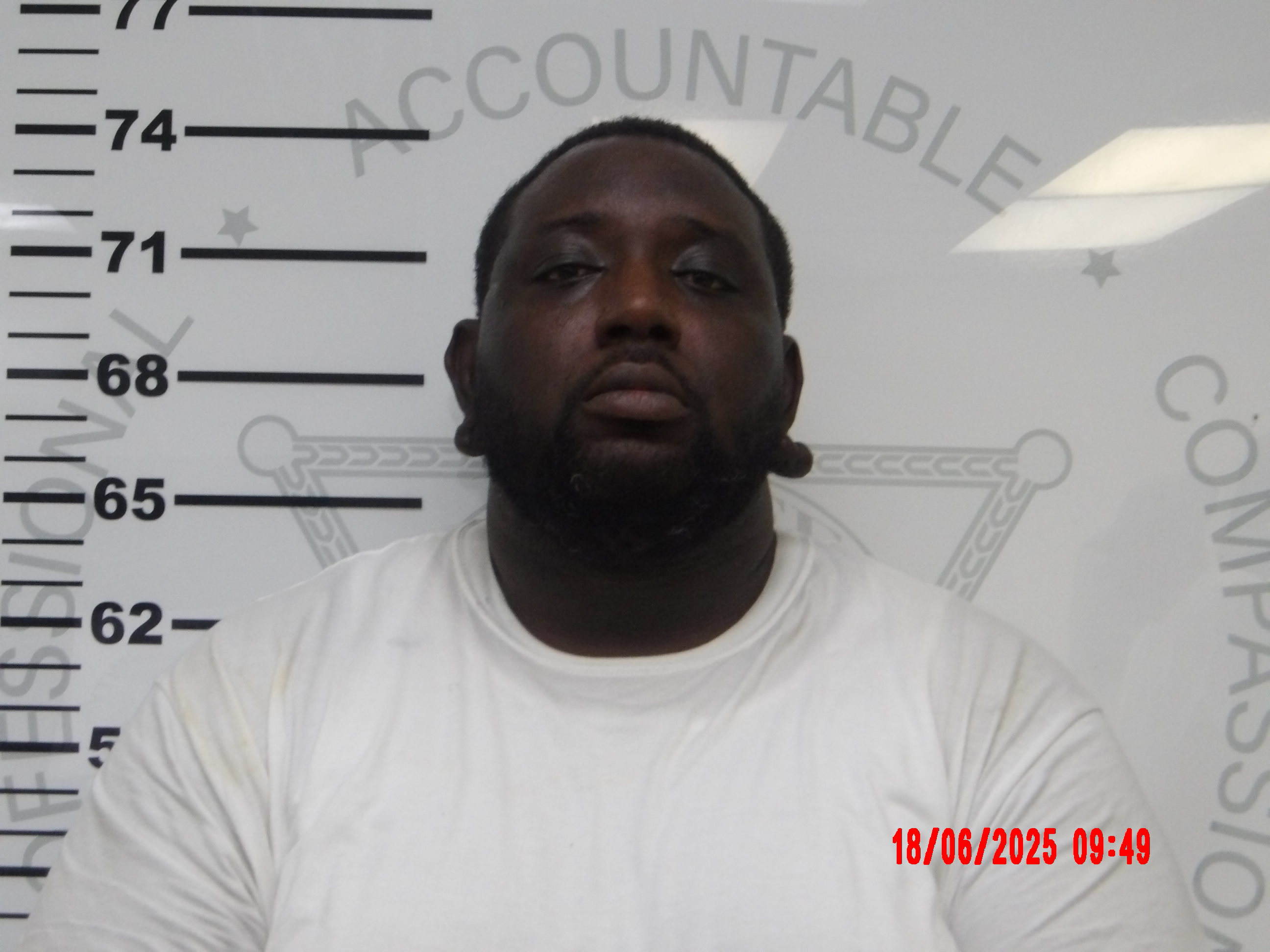

Branch is a Booneville native majoring in integrated marketing communications at the University of Mississippi and was recently named Ole Miss’ 2018 Most Beautiful. Branch has big dreams and she hasn’t let her circumstances define her or stop her. Instead, it has given her an opportunity to create a new organization at Ole Miss.

Serving Children of Incarcerated Parents (SCIP) is a work in progress, but aims to provide life-changing support for people who are going through similar situations as Branch.

“I would have never thought about doing this, but I finally realized that I need to make a difference and be a mentor for people who are in a relatable position,” Branch said. “A lot of people don’t have a support system; I was lucky enough to have my family’s support.”

However, family support still does not combat the emotional pain someone can feel when their parent is locked away.

It took many years to be comfortable enough to discuss her current situation, Branch said.

Not everyone is as fortunate.

Emotional challenges

According to Robert T. Muller, a professor of psychology at York University, a child’s attachment to their caregivers is important in social cognition, which is the study of how people’s thoughts and perceptions of others affect how they think, feel, and interact in everyday life.

Muller suggests that a person’s earliest thoughts about others are learned through their parents. Children who are raised without a sufficient parent-child interaction may lose important experiences. The child may have a difficult time socially and may experience emotional responses such as sadness, fear and guilt, which can turn into severe behavioral problems.

For Branch, there was a period where she felt that anger and confusion. She was bullied at school and teased for a situation she had no control over.

“I understand the struggles and pains that the children of incarcerated parents experience,” Branch said. “There were no resources available for me when I first faced this difficult time other than my family. I want to be a voice and a role model for the children who find themselves, by no fault of their own, in the similar scenario as I did.”

When someone in the family is incarcerated, it makes the rest of the family feel like they are imprisoned as well, Branch said.

Branch’s father was the breadwinner and left them in a financial burden with emotions that were difficult to comprehend.

Pageants and modeling enabled Branch to break through the barrier she had built up and shed light on incarceration.

She currently holds the title of Miss Tupelo 2018 and will be competing in the Miss Mississippi Pageant in June where she will advocate empowering children of incarcerated parents.

“Once I ended up in the Miss America organization, I sat down with my pageant directors and finally broke down the wall,” Branch said. “Until that day, I had never spoken with anyone about my father being in prison.”

Traveling across the state, Branch visited schools, clubs and churches to tell her story with her Miss Tupelo sash draped across her heart and her crown perched on her head.

“You never really know what someone else is going through,” Branch said. “When I tell these young kids that my dad is in prison, their jaws drop. But it creates a gateway for them to finally open up to me and share what has really been eating at them.”

Branch is just one out of the approximately 55,000 children in Mississippi who are impacted by an incarcerated parent, Dr. Randall Rhodes, Adjunct legal studies instructor at the University of Mississippi said.

“This is a huge problem,” Rhodes, who also serves as Chief juvenile officer for the 32nd Judicial Circuit of Missouri, said. “The heart and resilience of children in juxtaposition with the emotional stress and issues that follow having a parent incarcerated is what has kept me going at this job for thirty plus years. Just a little bit of mentoring can help them.”

SCIP’s mission

Incarceration rates aren’t just an issue in Mississippi, but across the nation. The national rate of incarceration is five times higher than any other country in the world, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Nationally, one in 28 children is impacted by an incarcerated parent and one in nine African-American children have an incarcerated parent, Rhodes said.

Branch wanted to be able to reach more people and realized that creating an organization with multiple members would impact more people than doing it alone.

Branch was introduced to Deetra Wiley, applications analyst-business communications specialist at Ole Miss and current SCIP advisor. Wiley, coincidentally, is a doctoral candidate working on her dissertation discussing students and children of incarcerated parents.

With their similar backgrounds, Wiley and Branch recognized that they could increase awareness of the needs of children with imprisoned parents, while providing resources and becoming a personal mentor to help to empower and find a safe haven for those children affected by parental confinement.

“Due to the mass incarceration and parental incarceration rates, there are many children left behind with single, foster, family members to raise them,” Wiley said. “We hope SCIP will facilitate and promote mentoring relationships with children whose parents are incarcerated, in order to enable those children to reach their full potential.”

Wiley’s father was incarcerated throughout her childhood up into her adult life at various intervals. She remembers feeling uncomfortable when some family members were not willing to speak the truth of her dad’s incarceration and tried to conceal it, but her father had taught her to embrace it.

“He was very influential in my life,” Wiley said. “Through weekly written letters, phone calls and frequent visits, I’ve been raised behind the bars, so to speak.”

Wiley recalls the continuous encouragement and inspiration he provided her. He encouraged her to read the Bible, especially Proverbs. He said to her “You were born to be a leader, and never be afraid face the world.”

Growing up in the Delta area in Mississippi, Wiley remembers she and her mother visiting with her father in a three-day house, a visitation program that allows inmates a three-day, two-night stay with their families, located at the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman.

In 2016, Wiley went back to the prison and found out that all of the programs that encouraged interactions between inmates and their families were gone.

“I thought to myself, ‘do they realize what they are doing?’ They are destroying families,” Wiley said. “Having those extended visitation hours and my parent’s conjugal visits preserved my family structure and is what got me and my family through our lives.”

Wiley saw a need for change.

Straight Talks

Wiley utilizes a program she calls “Straight Talks,” created as a way to remember the impact the visits with her father had on her, to spend time with members of her church, speak with them about their lives and well-being and find Bible verses that help them cope with what they are experiencing.

Because of her father’s impact on her throughout her life, Wiley also hopes to bring more attention to the parents in jail through her church’s monthly jail ministry as well as their children through SCIP.

One of SCIP’s many goals is to not only provide help to families who are dealing with the repercussions of imprisonment but to help those behind bars.

“Communication is key to have a positive upbringing,” Wiley said. “I am a living testimony of that and I want families who are going through what I’ve gone through to have the same opportunities I had.”

Wiley and Branch hosted their first event on campus to bring awareness of the group’s efforts in April 2018. Jayla Daniels, a senior psychology major from Austell, Georgia, attended the SCIP event to help support the cause.

Daniels is also very close to her family and sees the emotional effects an incarcerated parent has on her cousins. They do not open up about their feelings, but Daniels knows that they secretly struggle as their father has been in prison for 17 years.

The last time Daniels saw her uncle was two years ago, whenever he was allowed to attend his son’s funeral after his son was shot.

“No one was allowed to touch him or even give him a hug,” Daniels said. “He was only able to come to the funeral to take one look at his son and then had to go straight back to prison.”

Daniels used to be very close with her uncle and was hoping to get on the waiting list to see him during his visitation hours. With inmates limited to 10 visitors, Daniels was kicked off the list in order for his six children to see him. She hasn’t had contact with him since the funeral.

Love Letters

Due to the incarcerated parent’s inability to afford the necessary supplies, like pen and paper to talk to their loved ones, healthy communication is at a halt. To mitigate this issue, Branch started the “Love Letters” program, where she facilitates donations of paper, envelopes and stamps to incarcerated parents, enabling them to reach out to their children and rekindle their connection.

Timber Heard, a junior majoring in anthropology, also attended April’s SCIP event. Heard grew up in foster care and had friends who were put in foster care due to the fact their parents were incarcerated.

“I want to see SCIP do something with foster homes,” Heard said. “Growing up in foster care is tough. The kids who grow up like this, they usually go back to jail just like their parents because they don’t know how to survive in the real world. I think talking with kids is a good way to start. There is a cycle that needs to be broke.”

Janae Owens attended the event and was excited to finally see a group like this cater to her passion for serving others through community engagement. Owens is currently the program coordinator for the McLean Institute for Public Service and Community Engagement.

Similarly, Owens and Daniels both said that communication with any family member behind bars is not easy.

“A goal I hope that SCIP will consider is not just supporting the kids, but figuring out how to support an entire family unit because it affects everyone,” Owens said. “In order to change the child’s mind for the better, you got to change the people who are influential in their life too, like their parents.”

Growing up, Owens was surrounded by low socioeconomic families in Natchez. Throughout her life, she has seen a cycle of children with incarcerated parents follow their parent’s bad decisions and fall through the cracks.

Several of Owens’ siblings have been in and out of incarceration.

“Having a sibling go through that was life-changing,” Owens said. “I thought, ‘is this going to be me as well?’ But I figured out what path will I take to push me away from this. I chose getting my education. Then I had to ask myself ‘what role do I have’ to shed light on opportunities for my siblings, so they can pick up their feet again and not ever go down the same path or have their kids go down that path.”

Additional goals that Owens suggested is having the program connect with a course at Ole Miss. Any political science, psychology, or criminal justice class that would allow students to get some exposure to working with children of incarcerated parents. The work they would do with the program could correlate with what they are learning in the classroom.

“I look forward to seeing how far this goes in our community because it is needed in Oxford,” Owens said. “There isn’t a lot of exposure on this social issue that is happening in this very town.”

Wiley and Branch not only want to continue the programs they have already started but plan to institute service projects in association with the campus counseling center.

Eventually, Wiley and Branch hope to extend the group’s influence past the boundaries of Oxford and perhaps collaborate with other universities and other counties in Mississippi.

“We are hoping that eventually we can go to other areas around the globe and put our hands on anyone who is going through this,” Wiley said. “I’m thinking that if we can be vocal, change will come.”

“It is important that we move together, together,” Branch said. “To serve this population and become successful change agents.”