Holocaust survivor Marion Blumenthal Lazan speaks about her life, German occupation at Ole Miss’ Paris-Yates

Published 9:44 am Thursday, August 31, 2017

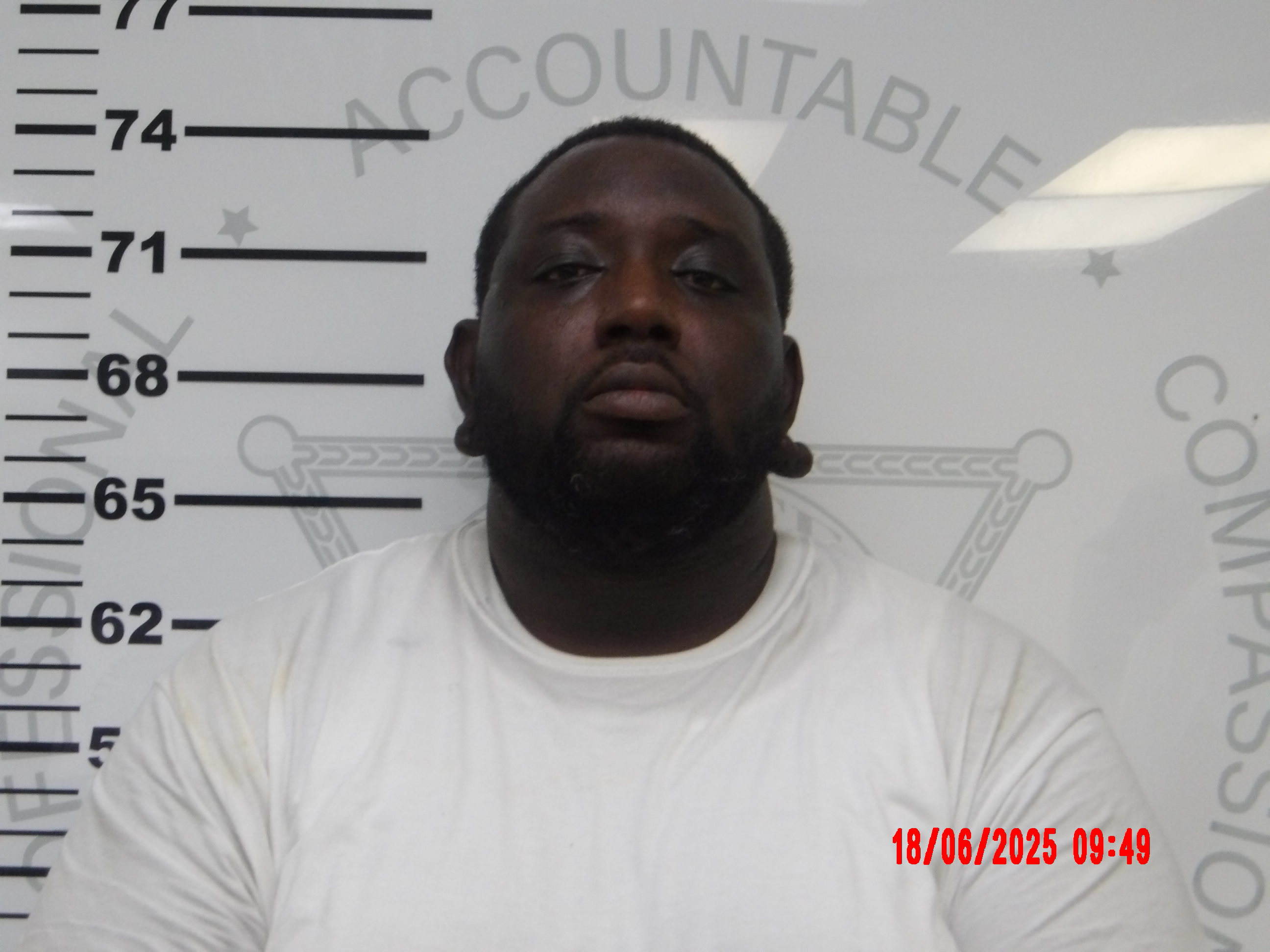

- Marion Blumenthal Lazan, author and Holocaust survivor, holds a picture of her mother before speaking at Paris-Yates Chapel on Tuesday. Lazan spoke to students in the Oxford and Lafayette County school districts, as well as to students at the University of Mississippi. (Photo/Bruce Newman)

The University of Mississippi recently hosted a speaker that is a member of the last generation affected by one of the greatest tragedies in human history.

Marion Blumenthal Lazan is a survivor of the Holocaust during World War II and the author of “Four Perfect Pebbles,” a book recounting her family’s harrowing experiences. She told her story to a filled Paris-Yates Chapel on Tuesday evening.

Blumenthal Lazan’s story began in the early ‘30s in Germany where she lived with her mother, father and older brother. Her father ran a successful shoe repair shop, but soon the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 put Jewish business owners and Jews under harsh restrictions.

“All public schools were closed to Jewish children,” Blumenthal Lazan said. “Then there was an evening curfew for Jews. Jews were only allowed to shop during certain hours of the day. Non-Jews were not allowed to shop in Jewish stores. A big letter ‘J’ for Jews was stamped on our ID cards and passports.”

By 1938, when she was 4 years old, her parents decided to flee the country and received their papers to travel to America. However, after Krystallnact (the Night of Broken Glass) on Nov. 9, 1938, when Germans destroyed Jewish business store fronts and other establishments, Blumenthal Lazan’s father was taken away by the Nazis. He was released after 10 days because he proved he had immigration papers in order to leave the country. Only a few years prior, her father had been awarded an Iron Cross for his service to Germany during World War I.

In January 1939, Blumenthal Lazan’s family moved to Holland where they were scheduled to finally travel to America. In the meantime, they were relegated to the Westerbork detention camp. In May 1940, one month before their planned departure date, the Germans invaded Holland and her family was trapped.

“All of our belongings which were being loaded onto the ship were burned and thrown into the harbor,” she said. “There was enough food for us in the camp at the time. Several months later, when the Nazis took over control of Westerbork, we became acquainted with the ever-present, terrifying 12-foot high barbed wire.”

Shortly after, in early 1942, transports to the concentration camps began. Two years later, her entire family was shipped out of Westerbork and sent to the camp Bergen-Belsen in Germany.

“We children were glad for a change in environment,” Blumenthal Lazan said. “We welcomed the move, we were very naïve. We were allowed to take one knapsack each. When we approached the platform and we saw the cattle cars in which we were to travel, our fears began to mount. It was a cold, pitch black night when we arrived at our destination.”

Bergen-Belsen was divided by gender and separated by electrified barbed wire. The barracks in which prisoners were forced to live were unsanitary and cramped. Two people had to share each bunk. Fortunately, for Blumenthal Lazan, she shared one with her mother.

“There was no privacy,” she recounted. “When we were in Bergen-Belsen, never once were we able to brush our teeth. Nor did we ever see a blade of grass.”

Malnutrition, lice, dysentery and death were common occurrences.

“We as children saw things that no one should ever have to say,” Blumenthal Lazan said, “I know you’ve probably read and seen movies about the Holocaust. But the constant foul odor, the filth, continuous horror and fear surrounded by death is indescribable.”

To pass the time, Blumenthal Lazan created a game based on superstition. It would eventually lend itself to the title of her 1996 book.

“I decided that if I were to find four pebbles about the same size and shape, then that would mean that all four members of my family would survive,” she said. “My mother, my father, my brother and I. It was a difficult game to play. What if I couldn’t find one of the pebbles? Might that mean that one of my family members would not pull through? Nevertheless, this game gave me something to hold on to. Some distant hope.”

As the war pressed on and the Nazis began losing ground against the Allies and the Russian army, prisoners were transported out of Bergen-Belsen to unknown destinations in the east. Blumenthal Lazan’s family was among the final group of 2,500 prisoners transported. After two weeks on a train ride she described as “horrifying,” the Russians liberated her family in April 1945.

The rescued family was taken to an abandoned farming village in Germany. At this time, Blumenthal Lazan was ten and weighed 35 pounds. Her mother weighed 70. Though her mother and brother survived, her father died from typhus six weeks after the liberation.

“When I talk about those years, it’s as if I’m reliving a nightmare,” she said.

When she was 13, her family moved to America in 1947 using the same tickets they had purchased a decade earlier. They settled in Peoria, Illinois and she graduated from the town’s high school at 18, despite the language barrier. The same year as her graduation, she married Nathaniel Lazan, who she met in Peoria when she was 16. They recently celebrated their 64th wedding anniversary earlier this month.

Her mother, who passed away four years ago, lived to be 104.

“Four Perfect Pebbles” is currently in its 29th printing and has been translated into dozens of languages, including Japanese.

“But above all, I’m so grateful that the story is in book form so that it can be passed on to future generations,” Blumenthal Lazan said. “Even after all the terrible things that happened to me as a child, my life is full and rewarding.”

Though she has spoken to upward of 1 million people, she says her story “still has not become easy” to tell.

“However, I do realize the importance of sharing that history with you,” Blumenthal Lazan said. “The Holocaust must be taught, must be studied and kept alive. Only then can we guard it from ever happening again.”