MANUEL AGUIRRE

Published 6:00 am Sunday, January 8, 2017

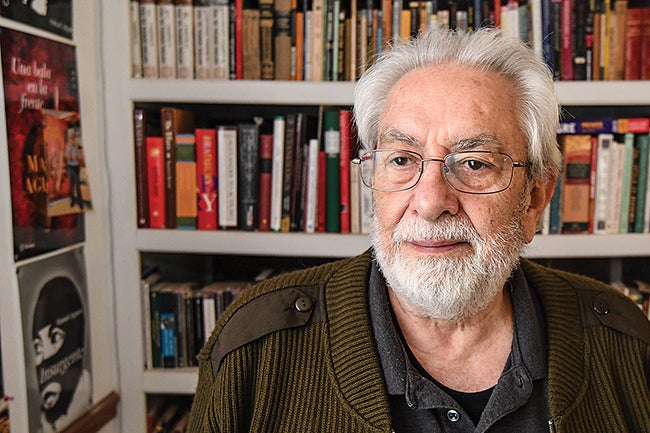

- Manuel Aguirre, an author from Peru, retired to Oxford in 2013 after spending several years abroad and leaving his home country amid death threats.

When he was in his early 20s, Manuel Aguirre served as a lieutenant with the Peruvian army in some of the most unforgiving terrain on the planet.

At 12,300 feet, the Altiplano is the second-highest mountain plateau in the world (behind the Tibetan Plateau), situated in the Andes Mountain range occupying Chile, Argentina, Bolivia and Peru. Low oxygen makes it difficult to breathe, there’s nothing to shield from the cutting winds and barely any plants sprout up from the ground.

“In the beginning, it was a very hard shock because of the environment and because of the altitude,” said Aguirre, 76, at his current home in Oxford. “I was with 10 soldiers and I was in charge. It was shocking for me. Imagine a guy coming from Lima (Peru’s capital), which was like Los Angeles.”

After a bad accident that almost left him dead, Aguirre recovered in a hospital bed for 15 days. He found solace in three books he found within a wooden storage box he had brought with him. The books were authored by Italian writer Giovanni Papini, a staunch critic of World War II.

“He opened my mind because before that I was only reading military books,” said Aguirre. “I read those books like a person who was in the desert with no water. I thought, maybe I can tell stories and draw from that shock and experience.”

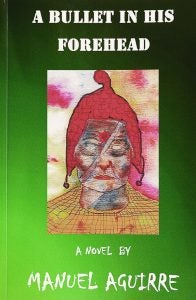

Writing became Aguirre’s pastime, but it wouldn’t be until decades later that he wrote a novel, “A Bullet in His Forehead,” fictionalizing his personal experiences in the Altiplano.

But the road to that book was long and, at times, unending for Aguirre.

World travels

After leaving the Peruvian Army in 1972, Aguirre married and had his first son. He moved to communist Hungary for one year before realizing that the dictatorship felt eerily similar to being in a military camp. What was intended to be a short trip to Spain, resulted in him and his family staying there for the next four years.

Aguirre moved back to Peru in pursuit of his MBA and eventually became a successful banker in the early 1980s. At the same time, a guerilla movement, Shining Path, began to form within the country and started to intimidate and extort some of the country’s elite living in Lima.

“Somebody decided to call my house and talk to my wife and asked for $100,000 or they threatened to kill me,” Aguirre said. “I was in a board meeting one day and my wife called saying they were outside the house.”

Threats continued until one day, Aguirre had enough after hearing about the death of his neighbor, an admiral, who was shot and killed at a traffic light. Aguirre decided to relocate his family to Los Angeles and in 1987, they made the move to the United States.

Finding meaning

The next few years, he worked as a contractor until he went back into banking as an underwriter. The grueling hours of the profession began to take a toll on his life.

“I began to think that life had no meaning,” he said. “For me, happiness and effort should be rewarded. And I thought, what purpose do I have in life? It wasn’t depression, it was an ideological problem. I decided to create a project and I wanted the project to last five years. I decided to write a novel.”

That novel became “Doubts and Murmurs” and clocked in at 1,200 pages when it was completed in 1998. He wrote the immense book during the one-hour lunch break of his 12-hour workdays and immediately when he got home at night.

Aguirre who calls himself, “naturally obsessive,” says it was all he could think about.

“Three years later (in 2001), I understood that the novel wasn’t good enough to print,” he said. “But after all those years of intense dedication to writing I had learned how to write a good novel.”

He then began working on “A Bullet in His Forehead,” which was then published in Lima in 2006 and was later translated into French. A noted French literary critic, Mathieu Lindon, reviewed the book with overwhelming praise in 2010 for the Paris paper, Liberation.

When Aguirre found his way to Oxford in 2013 to retire with his wife, he met a friend, Bill Staton, who encouraged Aguirre to have his son, Santiago, translate the book into English. That version came out this year and is available for purchase on Amazon.

Readers of the book have favorably compared Aguirre to Fyodor Dostoevsky, the acclaimed Russian novelist whose works dealt with philosophical and religious themes.

Aguirre is humble about it all.

“I don’t write to be a millionaire,” he said. “I write to get my books down in an endurable form. I’m searching for remote contact with other people.”