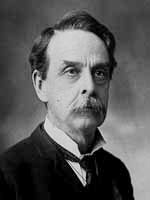

L.Q.C. Lamar elected back to Congress in 1873

Published 6:00 am Sunday, November 20, 2016

With the Congressional elections this past week, I thought I would pass along some historical data on Lamar’s return to his old seat from the 1st Congressional District of Mississippi.

After the end of the Civil War, Lamar felt his life in “public service” was over and the removal of his political disability before he was able to take his old seat in the U.S. Congress would pose a large roadblock to his return to “public service.”

The provisions of the 14th Amendment disqualified Lamar from holding public office. He was very despondent after the war and he felt he was now destined to be a country lawyer and a professor at the state university located in Oxford. In his biography of his father-in-law, former Chancellor Edward Mayes writes of this time in Lamar’s life he was in a state of limbo at his home on North 14th Street in Oxford

Mayes writes of Lamar being seen by his friends and neighbors at home, leaning on the picket fence that was in front of his home, “clad in a drab study-gown, somewhat frayed and stained with ink; resting against the fence, learning as if wounded, with his strong arms flung carelessly over it for support, and his head drooping forward … a countenance solemn, sober and enigmatical.”

He was very despondent about the “vile vampires who were drawing the life-blood from his prostrate state.”

Lamar knew if he wanted to re-enter the field of public service he would have to call upon Congress to live his political disabilities. This was no small chore since no former Congressmen or Senator from a state, which had been so recently in rebellion had tried to take over their old seat in the Federal legislative houses of government. If Lamar were to do so, he would be a trailblazer for others who wished to return to Congress.

A chance of fate would soon come which would bring him back before the people of the 1st Congressional District of north Mississippi. A speech he would be called to make, due to the illness of a Democratic friend, would thrust him again into the spotlight and open a way for him to re-enter public service by canvassing for his old House of Representatives’ seat.

On Oct. 9, 1871, a meeting and speeches were being held on the Courthouse grounds in Holly Springs. Gov. James L. Alcorn and Robert Lowery were meeting in a debate. Lamar happened to be in town on business and was in the audience and his fellow Democratic Party friend, Lowery, was taken ill. Lamar’s young law partner, E.D. Clarke, called upon Lamar to “represent the Democratic champion in this emergency.” Lamar was again forced, by circumstances and not by his will, back into the heated arena of politics. It caused him to rethink running for his old Congressional seat.

A movement began to take hold to send him back to Congress. It was helped by many newspapers in his region of Mississippi and in the state capitol. There was much hesitation by men, who otherwise, would have been ardent supporters, but the wish for him to re-enter the political fray was so strong, and also the confidence in his abilities and patriotism so great.

At a convention held in Tupelo in late August 1871, after a number of votes were taken over two days, he finally received a unanimous vote to be the Democratic Party standard-bearer. His opponents in the election were Republican Col. R.W. Flournoy and the editor of a Water Valley newspaper, R.M. Brown.

Lamar would make many speeches throughout the district but the problem with his political disability was always on his mind. He garnered support from both Democrats and Republicans. His re-entrance into politics attracted attention in other states and numerous congratulatory notices appeared in prominent Southern journals. On November 4, 1872, he was elected by a majority of nearly 5,000 votes. Now, came the problem of his disability and a vote in Congress.

In December, he made his way to Washington in order to press his application for relief from his political disability. He did not know how the Northerners in Congress would receive him. His anxiety over the vote was not warranted. Within four days, the House voted to remove his disability by a vote of 111-13, and the Senate passed the bill to remove his disability by unanimous consent. He was now ready to take back his old seat in Congress.

No sooner had the bill passed; Lamar was again seized with vertigo in a very severe form. The infirmity came at times immediately after relaxation of some great nervous tension as it had after the Battle of Williamsburg in 1862. This time it would almost take his life. Luckily, a friend from his earliest days in Mississippi came to his support.

Dr. Albert Taylor Bledsoe, who had been one of the first faculty members at the new state university in Oxford and the man who took over as the interim head of the university when George F. Holmes failed to return to the university in 1849, was now the editor of the “Southern Review” and lived in Alexandria, Virginia. He and his wife took Lamar into their home and nursed him back to health. Although for several days, it looked as if the end had come, Lamar’s strong constitution finally prevailed, and his health slowly returned.

During the next year, 1873, Lamar pondered most carefully and anxiously over his future course in Congress. Mayes writes of Lamar’s question to himself, “How could I best help onward the cause to which I am now consecrated: The perfect reconciliation of the North and South? That was the overwhelming problem.”

The death of a radical Republican and ardent abolitionist, Sen. Charles Sumner, in 1874 and Lamar’s eulogy of him on the floor of the House of Representatives would become the “perfect reconciliation” between the two sections of America who fought the great, bloody battles of a civil war.

Jack Mayfield is an Oxford resident and historian. Contact him at jlmayfield@dixie-net.com.