Summing up Opioid Summit: If doctors don’t restrict prescriptions, lawmakers will

Published 4:14 pm Saturday, July 15, 2017

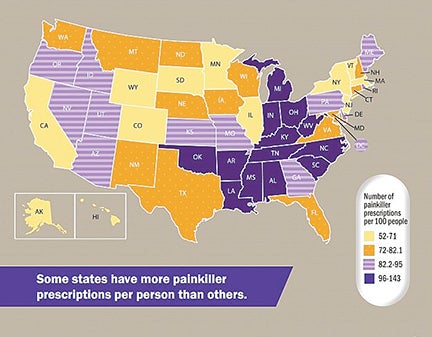

- Mississippi is among the national leaders in painkiller prescriptions with 120 per every 100 people, according to the Center for Disease Control. Alabama and Tennessee lead the nation with 143.

BY LARRISON CAMPBELL

Mississippi Today

Nearly every one of the more than two dozen speakers at this week’s Opioid Summit in Madison agreed on one thing: If Mississippi is going to get a handle on its growing drug problem, doctors must swiftly curb the number of opioids they prescribe.

In 2014, health care providers in Mississippi wrote 3.36 million prescriptions for opioids, which translates to 1.1 prescription for every resident in the state. This is the fifth highest opioid prescription rate of any state in the country.

One of the best ways of reining in the problem, according to these same experts, is making doctors and pharmacists fully use the state’s prescription monitoring program, which gives providers a record of a patient’s prescription history. Providers are required to submit patient information to the database, which was implemented in 2005, but they are currently not required to check it.

In his opening remarks Tuesday, Attorney General Jim Hood urged health care providers to check the database every time they write a prescription. But Hood stopped short of calling for a statewide law that would require them to do that, which other states have done.

Instead, he said, the boards that govern doctors, pharmacists and nurses should write their own rules.

“We have to curb the numbers of prescriptions but give doctors the flexibility to create their own regulations,” Hood said.

Over the course of the three-day summit at Broadmoor Baptist Church in Madison, several speakers reinforced the idea that when it comes to curbing the opioid problem in Mississippi, health care providers, not legislators, are best equipped to spearhead changes.

In some ways this reflects the make-up of the event itself. Mississippi’s first Opioid Summit was a partnership between four state agencies: the Attorney General’s Office, the State Medical Association, the Bureau of Narcotics and the Department of Public Safety.

But it also highlights the frustration that some medical professionals feel over the inefficiency of the state’s lawmaking body, especially when responding to a mounting crisis.

“Extreme care always has to be made in looking at legislative changes because legislation is, by its very nature, not very flexible,” said Steve Parker, deputy director of the Board of Pharmacy. “So the first line of defense in this arena is to attempt to allow the regulatory agencies to implement these changes because they can more readily act.”

The lawmaking process is also one of revision, and amendments can make the final version of a bill unrecognizable from its first draft.

“This is not a knock on the legislative process, but so many times if you have a piece of legislation that goes into law and it ends up being a bad piece of legislation, it’s hard to reverse it,” said John Dowdy, director of the Bureau of Narcotics and chair of the Governor’s Task Force on Opioid Addiction.

“In our study and in other states we have seen that happen, where there may have been legislation (passed) into law that was not intended,” he said.

The often highly addictive opioids are a family of the painkillers derived from the morphine molecule, including morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydrocodone and heroin. Mississippi is one of just 12 states where the number of prescriptions exceeds the number of people in the state.

“That is a lot of prescriptions, more than anyone needs,” said Meg Pearson, a director at the Mississippi Department of Health, who spoke about opioid prescription rates and trends.

‘Heroin is coming’

In 2015, 35 people died of heroin overdoses in Mississippi. While this is a record number for the state, it’s just a fraction of the number seen in states in the heart of the epidemic. In Ohio, 1,424 people died of heroin overdoses that same year.

And high prescription rates ultimately lead to high rates of heroin addiction. According to speaker Sam Quinones, whose book Dreamland chronicles the nationwide opioid epidemic, 80 percent of heroin users used prescription opiates first.

“Heroin is coming,” said DeSoto County District Attorney John Champion.

Cutting down on prescriptions is one of the best ways to prevent more addictions, according to Dowdy. Parker calls the Prescription Monitoring Program “one of the most important tools in our toolbox.”

According to Pearson, another tool that will curb prescriptions is education, specifically training health care providers to recognize that opioids should be given only for extreme pain.

“Training rather than laws,” she said, will be far more effective in changing doctors’ prescribing practices.

Retraining doctors

In the late 1990s, medical schools and journals, spurred in part by misleading studies and heavy marketing from prescription drug companies, began advocating for aggressive pain management, which often meant opioids. In 1999, the Veteran’s Administration declared “pain” the fifth vital sign, along with heart rate, respiration, temperature and blood pressure, and doctors were instructed to use pain as an indicator of a patient’s overall health.

“You have to understand that a generation of doctors went through training under this idea, so now we have to retrain them,” Pearson said. “I believe most doctors are acting with good intentions.”

To this point, the Board of Medical Licensure has added five hours of substance abuse training to its Continuing Medical Education requirements, and the Board of Medical Licensure holds continuing education clinics throughout the state.

“Doctors tend to take care of illnesses the same way we were trained,” Easterling said. “The way you do things now should be different than the way you did things 30 years ago.”

The emphasis on education over legislation extends to the treatment of patients with substance abuse disorders. Several panelists spoke about the problems with current standards of care, which require a patient to get well within a finite period, usually a 30- or 45-day stay at an inpatient rehab facility.

“So we’re saying that abuse is a chronic disorder but we’re treating it like it’s strep throat,” said speaker Marsha Stone, the CEO of BRC Recovery in Austin.

“If it’s a chronic illness, let’s start to treat it like it’s a chronic illness,” she said.

Easterling agrees. He said educating physicians about the benefits of long-term treatment when dealing with an opioid addicted patient is a priority for the Board of Medical Licensure.

“The key to that is follow-up,” Easterling said.

“We want to encourage them to look at the practice patterns and be willing to change those practice patterns,” he said.

But fixing this is a bit of a Catch-22. Doctors can change how they think about addiction, but they won’t be able to change how they treat it without funding. And Easterling acknowledges that the Legislature ultimately holds the purse strings.

“At the end of the day any legislature in the state — and the federal government — defines what we can and cannot do, and we serve at their pleasure,” Easterling said.

The Department of Mental Health currently funds 32 recovery programs across the state through their Bureau of Alcohol and Drug Services, at an annual budget of $21 million. In 2016, the Department of Mental Health shuttered their one male inpatient chemical dependency unit, citing budget constraints.

But knowing that lawmakers have ultimate authority has motivated the Boards of Medical Licensure, Nursing and Pharmacy to take action, Easterling said.

“I’ve been very sore with my colleagues that if we don’t fix this they’re going to fix it for us. And that’s not something that’s going to be beneficial for the providers or the patients,” Easterling said.

Hood agrees, saying if the agencies don’t act, he’ll make sure the legislature does.

“The licensure boards are perfectly capable of policing their own licensees through appropriate rules and regulations and should be given the opportunity to do so. At the same time, we cannot ignore the value of the PMP (Prescription Monitoring Program) if it is checked,” Hood said in an email.

“I am prepared to push legislation if the licensure boards do not take adequate steps to help address the crisis we are facing. We simply cannot arrest our way out of this crisis. We have to address the problem where it begins (the prescription) as well as after an addiction results through appropriate treatment.”

Lawmakers, for their part, were largely absent from the Opioid Summit, although every member of the Legislature was invited. Representatives from the lieutenant governor’s office were present as were representatives from the speaker of the house’s office, though neither official attended.

Dowdy called the event “indescribably huge,” in Mississippi’s efforts to get ahead of the crisis.

“I feel strongly that we have started a movement that is going to ensure that Mississippi takes care of Mississippi but also steps up as a national leader in the fight of opioid addiction,” Dowdy said.